How many types of slate are there? Let’s explore all their characteristics and differences

We already know that there are several types of roofing slate in the world, and that they are not all the same in terms of quality and versatility. As we have said before, not all roofing slates are slate.

Slate for roofing is a metamorphic stone that can be split into thin tiles to be installed on a roof. There are several rock types in this group: metalutite, slate, phyllite, mica-schists, quartzite… they are not the same and each has its own characteristics. “Roofing slates” is the name of a group of rocks, not just a single type of rock, although it is true that most “roofing slates” are slates.

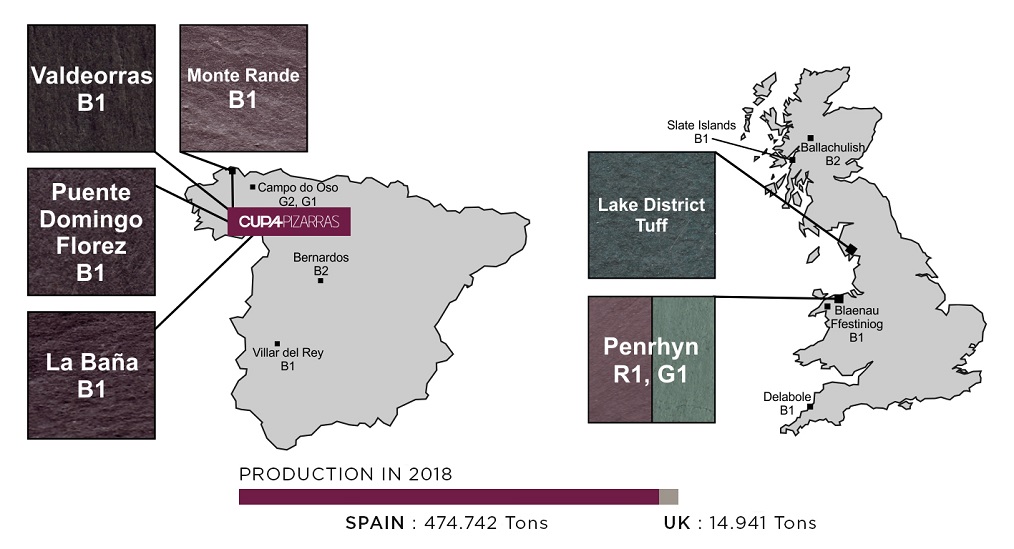

Broadly speaking, roofing slate varieties can be identified with specific countries. For example, the lithotype of roofing slate in Spain is B1 which, according to the International Roofing Slate Classification (IRSC), is an authentic slate which is black-grey in colour, fine grained, homogeneous and highly fissile, enabling its splitting into thin, regular slabs.

International Roofing Slate Classification

The extinct deposits in France and Germany also produced this lithotype, which usually has a half-life close to 100 years and great resistance to alteration. B1 also has low water absorption (0.3%) and high flexural strength, at over 50 megapascals (MPa) on average, in many cases reaching 70 MPa. Another feature is the clean, crystalline sound produced by the slabs of slate when they are hit with a metal object. This sound indicates that the internal structure of the slate is solid and has no imperfections. If it did have, the sound would be deeper and the slate would sound hollow.

Lithotype B1 is the dominant type in Spain, but not the only one. Production of this lithotype is estimated at around 98% of total production, representing about 473,000 tons in 2020 (AGP data). The remaining 2% is of lithotypes B2 and G2, the black-grey and green phyllites produced at Bernardos (B2) and Bretoña (G2 and B2).

A house with spanish slate roof type B1

These lithotypes have properties similar to B1, but with a higher degree of mineral crystallinity. This means phyllite has a characteristic brightness, which is more accentuated than that of slate, but on the contrary, it has greater rigidity and therefore fragility, although it easily reaches bending strength values of over 50 MPa. The phyllite deposits are much smaller than those of slate, which means production of this rock is much more limited.

Two other characteristic lithotypes are produced in Europe: R1 (purple-red slate) and G1 (green slate). Like the B1, these are authentic slates, but with different mineralogical composition, which gives them their characteristic colours. There is now only one quarry left in Wales that produces this type of slate for roofing.

Main deposits and slate types in Spain and the United Kingdom.

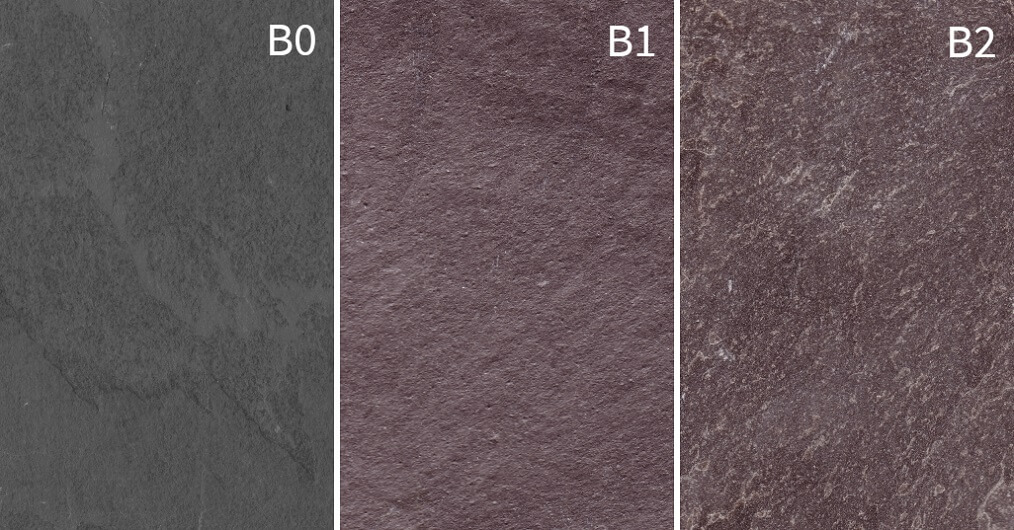

Brazil also produces “roofing slate”, but these are of very different lithotypes from the Spanish. The Brazilian lithotypes are B0, G0 and, to a lesser extent, R0, that is, black-grey, green and purple metalutites.

Metalutite is also a rock of metamorphic origin, which can be split and used as “roofing slate”, although from the geological point of view it is not an authentic slate. This is a rock of a lower metamorphic grade, less crystalline, which translates into lower bending strength values than those presented by authentic slate. When hit, it produces a more irregular and deeper sound, more “hollow-sounding”, and its water absorption is around 0.8%. Although this is still low, it makes it more vulnerable to ice-thaw cycles than the authentic slate and phyllite.

It has a very characteristic texture, with a rough, matte surface. This is because it has not undergone the same degree of metamorphic crystallisation as slate or phyllite, and its minerals have not crystallised in an apparent manner. This lack of metamorphic recrystallisation is clearly seen in the bevelling of the slabs, which is much more irregular and erratic than that obtained in true slate. This means that slate installers cannot cut the slabs properly when they are working on a roof, so these lithotypes have very low acceptance in countries such as Germany or France.

B0: brazilian metalutite, matte appearance, rough surface

B1: Spanish slate, fine, glossy surface

B2: Spanish phyllite, the surface scales are produced by the greater metamorphic recrystallisation

Finally, China also produces “roofing slate”. The production, quality and lithotypes from this country vary enormously, and are a real mystery. China is a huge country, with a wide variety of rocks, including deposits of all the roofing slate lithotypes in existence. The lack of infrastructure and specialised personnel results in highly irregular production from the country.

On more than one occasion I have heard complaints about poor (or lacking) production homogeneity. The most frequent comment is that initial shipments of slate have an acceptable degree of quality, but this changes rapidly in later shipments. While China’s potential is undeniable, buying slate for roofing in this country today is a risk that few dare take. The Chinese Government is reorganising the sector, which could lead to improvements its quality parameters in the coming decades.

In any case, China will never be able to offer a product of better quality than slate produced today in Spain. This is an undeniable fact.

There are things where saving works out expensive, and roofing is one of these. A product of poor or low quality will end up giving problems, which will result in the need to invest extra money and resources. It is better to use a good slate from the start, backed by a sound, reliable company, so your roof never becomes a problem.