NOT ALL SLATE

IS CREATED EQUAL

Brazilian metalutite: not a natural slate

Independent authorities across the roofing industry — including the NFRC and leading geologists — have clarified that what is often sold in the UK and Ireland as “Brazilian slate” is actually a different type of rock: metalutite.

Regulatory data, laboratory testing, and documented cases indicate that this material presents technical, economic, and environmental risks when used in roofing applications:

The risks of Brazilian metalutite are explained and documented in the ‘Technical report on Brazilian metalutite’ published by the Cluster de Pizarra de Galicia (Spanish Association of Slate Producers) and confirmed by regulatory data, laboratory tests, universities, trade associations, and insurers, all documenting its failures:

We can help you understand the differences between natural slate and Brazilian metalutite and make the right choice for a durable, long-lasting roof.

A geologically distinct rock

Unlike true slate formed by tectonic metamorphism, Brazilian metalutite comes from compacted sedimentary materials. It may look similar, but geologically it is a completely different rock.

Details & References

The rock quarried in Brazil (originating from Minas Gerais) is metalutite, a mudstone subjected to incipient metamorphism that cleaves along its original sedimentary plane, S0¹. In contrast, true slate forms within orogenic belts and oriented tectonic pressure strengthens the rock. It aligns the phyllosilicates and generates a continuous metamorphic cleavage plane, S1 which is the foundation of its structural cohesion and of the fine lamination for which it is widely recognised. It is precisely due to this structural distinction that the European standard EN 12326-1 recognises only rocks with metamorphic cleavage as “slate,” explicitly excluding those that split along the S0 plane.

Petrographic studies conducted by Dr. Mesones³ on the quarries of Minas Gerais confirm that the material in question, metalutite, is of low metamorphic grade. This assessment is echoed by the UK’s National Federation of Roofing Contractors (NFRC), which states: ‘Brazilian slate is a metalutite made from mudstone… it has not gone through the whole metamorphic process that true slate has gone through’². In summary, Brazilian metalutite and tectonic slate are geologically two entirely distinct rock types⁴.

Sources:

1: EN 12326 1:2014 – Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding. Part 1

2: NFRC Guidance Note GN 66 – “Brazilian slate”

3: “Lithostatic Comprehension” Report (FCTP, 2016)

4: Dossier “Brazilian Metalutite vs Spanish Slate” (Cardenes et al., 2023)

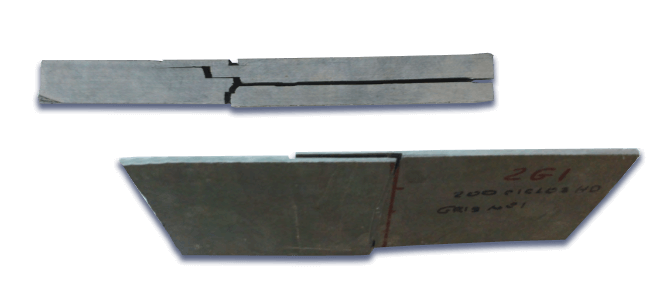

Why Brazilian metalutite falls short: breakage and spontaneous delamination

Brazilian metalutite has not been reinforced by the same tectonic processes that give true natural slate its strength. Under load or exposure to the elements it can open like a book and lose almost half of its strength. It is installed with hooks to try to mitigate the problem, but it does not eliminate it.

Details & References

The flexural tests of the Slate Technology Centre¹ show that, after 200 freeze-thaw cycles, the average strength of the metalutite drops from ≈ 55 N/mm² to ≈ 32 N/mm² (41 %) and abnormal fractures, total delamination and edge cracks appear. EN 12326 2² considers such a shear fracture undesirable because it invalidates the strength calculation. The NFRC³ for the UK and Ireland warns that the stone is ‘more brittle than European slates’ and recommends hook fixing to reduce the risks that can occur when the slate is installed with the traditional nail fixing.

Experts and installers repeat the same mantra: ‘hook all Brazilian slates, they crack’⁴. At the mineralogical level, the absence of S1 cleavage explains why the longitudinal and transverse values are almost identical (≈ 53 MPa)⁵, confirming the lack of ‘grain’ that strengthens true natural slate. In short: poor internal cohesion → unexpected breaks → need for non-traditional fixing systems which do not solve the problem.

Sources:

1: “Lithostatic Comprehension” Report (FCTP, 2016)

2: EN 12326 2:2011

3: NFRC GN 66 – “Brazilian slate”

4: Boards.ie Construction forum (2010)

5: Brazilian Metalutite vs Spanish Slate (Cárdenes 2023)

Note: Images extracted from “Study about the behavior of lithotomic compression slates” with authorization from the Cluster da pizarra de Galicia.

Water absorption and frost damage: metalutite does not withstand British weather

A roof is the first line of defence against the elements. In regions with heavy rain, snow, frost, and low temperatures, that protection must be reliable. Brazilian metalutite absorbs water, swells, and fractures, making it incompatible with the climate of the UK and Ireland.

Details & References

Brazilian metalutite absorbs almost twice as much water as tectonic slate (0.77% vs. 0.28%)2; in freeze/thaw tests at the Slate Technology Centre1, its black variant went from 0.55% to 1.19% absorption and lost 41% strength after 150 cycles, with fractures in three specimens and total delamination of another from the 6 samples tested. The grey variant repeated the pattern: with a reported absorption of up to 0.61 % and a fall to 35 MPa in 200 cycles. In EN 12326-15 any stone that exceeds the threshold W1 ≤ 0.6 % must pass freeze-thaw tests; if it shows delamination or structural splitting, it is not of acceptable use.

The NFRC3 warns that the ‘higher rate of water absorption’ of metalutite makes it ‘vulnerable to freeze-thaw cycles’ and requires extreme care during installation. This is exacerbated by the fact that an average UK winter accumulates prolonged freeze-thaw cycles over weeks, with nights below 0°C and days with positive temperatures, with the metalutite saturated with rain4. The result: cracking, flaking and shortened service life, not acceptable for the functionality of a roof.

Sources:

1: “Lithostatic Comprehension” Report (FCTP, 2016)

2: Brazilian Metalutite vs Spanish Slate (Cárdenes 2023)

3: NFRC Guidance Note GN 66

4: EN 12326 1:2014Roof Tile Association – Choosing roofing materials for the UK climate (2019)

Metalutite lacks the thermal resistance needed for the British climate

Tests show that Brazilian metalutite can lose up to 60% of its strength and starts to flake and split after repeated cycles of heat and cold. The result is cracking, surface damage and a roof that fails long before it should. Industry standards even classify these failures as unacceptable for any roofing material.

Details & References

Thermal cycling tests conducted by the Slate Technology Centre1 subjected black and grey metalutites to 0-100-200 cycles of immersion in water at +20°C, followed by heating to +110°C. The black variety saw its average resistance decrease from 57.2 N/mm² to 40.6 N/mm² (-29%), while its attributed resistance plummeted from 44.8 to 4.0 N/mm² (-91%). Furthermore, abnormal breakages due to delamination and fragmentation appeared in 4 out of 12 samples upon reaching 200 cycles. The grey variety exhibited a similar pattern: its average resistance dropped from 54.9 to 35.3 N/mm², and it experienced multiple abnormal breakages.

The EN 12326-12 standard deems only those pieces classified as T1-T2 after thermal testing to be acceptable2,3. Samples exhibiting ‘exfoliation, splitting or other structural changes’ are considered unfit for use. The majority of metalutites tested demonstrate precisely this exfoliation, which means they should not be commercialized as slate according to the standard.

Sources:

1: “Lithostatic Comprehension” Report (FCTP, 2016)

2: EN 12326 1:2014 – Code Table T1 T3

3: NBS – “Roof slates and BS EN 12326”

4: Lithostatic compression – Test Methodology

Metalutite: inconsistent thickness, harder installation

To reach the minimum values for roofing, metalutite needs almost twice the thickness of tectonic slate, which adds unnecessary weight and makes it difficult to install. A major problem is that the metalutite that reaches the UK market does not always maintain these thicknesses, leading to high uncertainty about its actual performance.

Details & References

The EN 123261,2 standard calculates the minimum thickness according to strength and climate. While a tectonic slate for the United Kingdom can be as thin as 4-5 mm, metalutite with the same strength must be ≥ 8 mm when it achieves the S3 code (typical exposure in a UK urban atmosphere). Studies by Dr Cárdenes4 confirm that Brazilian rock only exfoliates regularly from 6 mm upwards, compared to <3 mm for European slate. Increasing the thickness increases the weight of the system by up to 50%, forcing structural reinforcements and more expensive transport.

Moreover, the NFRC3 warns that “Brazilian slates cannot be cut with traditional hand-cutting tools due to their thickness and density”. Furthermore, tests conducted by the Slate Technology Centre reveal abnormal breakages in samples measuring 5–6 mm. This pushes producers to submit even thicker samples to pass tests. The slate that arrives in the United Kingdom often has actual thicknesses of 5-8 millimetres, a thickness that fails to comply with testing standards and presents a risk of quality issues5.

Sources:

1: EN 12326 1:2014 – 5.2.3.4 and Example 44

2: EN 12326 1:2014 – Table 1

3: NFRC Guidance Note GN 66 (2023)

4: Brazilian Metalutite vs Spanish Slate – § 2.1 Cutability

5: “Lithostatic Comprehension” Report (FCTP, 2016))

Not just theory: documented problems with metalutite in the UK

The issues associated with Brazilian metalutite in the United Kingdom are well-known and documented. Insurers, trade associations, and users have reported instances of breakages and detachments in roofs utilising this material. Consequently, the NHBC excluded it from their warranty in 2012, and the NFRC has issued warnings regarding its delamination since 2013.

Details & References

The NHBC1, the largest home insurer in the United Kingdom, has warned since 2012 that certain “slates from Brazil” fall outside the scope of EN 12326 and are not accepted on homes covered by their policy1. The NFRC corroborated this issue in 2013 and documented it in their NHBC Technical Extra 072 and Guidance Note GN 662. They state that Brazilian stone exhibits a “higher rate of water absorption” and “has been found delaminating on various properties.”

This warning is echoed by businesses within the sector: Ashbrook Roofing3 references the NHBC bulletin and NFRC alert following ‘Brazilian slates that were delaminating.’ In technical forums, installers recommend ‘hooking all Brazilian slates’ because ‘they crack’4, and even users of the PistonHeads forum recount ‘high-end’ roofs where Brazilian pieces ‘fall off after a few months… avoid Brazilian slate like the plague.’4 The pattern is clear: there’s a documented history of failures and incidents, acknowledged by the national insurer, installer federations, and industry professionals themselves. The consequences are serious; from an expensive a water leak in a roof5, to a detachment can cause injuries to people and have significant legal repercussions.

Sources:

1: NHBC Technical Extra 07 (Jul 2012)

2: NFRC Guidance Note GN 66

3: Ashbrook Roofing blog (Sept 2023)

4: Boards.ie Construction forum (2010)

5: PistonHeads –Homes & DIY Forum (May 2020)

Hidden costs: higher pollution and lower quality control

A container of Brazilian “slate” emits approximately 705 kg of CO₂ when crossing the Atlantic, compared to only 171 kg of CO₂ if the slate originates from northwestern Spain. Furthermore, the NFRC and the Stone Federation warn that the documentation of origin and test results for some Brazilian consignments is often incomplete.

Details & References

The geographical origin of materials significantly impacts their environmental footprint and supply chain transparency. Shipping routes from Brazil to the UK, for instance, average 705 kg of CO₂ per TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit), whereas routes from Spain to the UK emit a mere 171 kg of CO₂ for the same cargo—nearly four times fewer emissions1,2. Research by the Stone Federation confirms that transportation is the primary factor escalating the carbon footprint of imported materials, particularly when compared to stone quarried within Europe3.

Regarding transparency, the NFRC GN 664 advises demanding “traceability and independent test certificates” because several Brazilian consignments have arrived without complete documentation. This recommendation aligns with the Stone Federation GB’s ‘Selecting the Correct Stone’ guide, which mandates that every sample be labelled with its traditional name, quarry, and country of origin5. The guide further warns: ‘if the supplier does not provide this information, it is recommended to choose another stone.’

In essence, each shipment of metalutite contributes more CO₂ and offers fewer guarantees regarding its origin and testing procedures. In contrast, the more direct access and stringent labour and quality regulations in Europe make continental tectonic slate a material with a lower environmental impact and processes audited from extraction to CE marking. With metalutite, distance and opacity add carbon emissions and significant uncertainties.

Sources:

1: FluentCargo – Route Brazil → UK (accessed May 2025)

2: FluentCargo – Route Spain → UK (accessed May 2025)

3: Stone Federation GB – “Natural Stone. The Oldest Sustainable 4: Material” (2011)

4: NFRC Guidance Note GN 66

5: Stone Federation GB – “Selecting the Correct Stone” (2011)

Still have questions? Our technical team is always available to help you choose with confidence.

REFERENCES

The information presented in the Technical Report on Brazilian Metalutite, published by the Cluster de Pizarra de Galicia (Spanish Association of Slate Producers), is thoroughly documented and supported by the following technical articles, specialized publications, and other authoritative sources.

Details & References

Ashbrook Roofing Supplies. (2023, September). Brazilian slate: Which ones are useable? Retrieved 16 June 2025 from Brazilian Slate: Which ones are useable? — Ashbrook Roofing Supplies LTD

Boards.ie. (2010, July 28). Natural slate: nail or hook [Forum post]. Retrieved 16 June 2025 from Natural slate: Nail or Hook — boards.ie

Cambridge University Press. (2011). Metamorphic rocks: A classification and glossary of terms (Fettes, D., & Desmons, J., Eds.). Cambridge, UK: IUGS Sub-commission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks.

Cárdenes, V. (2025). Brazilian metalutite versus Spanish slate: A comparative study [Unpublished internal report, Department of Geology, University of Oviedo]. Copy on file with the Slate Cluster of Galicia.

Cárdenes, V., Cnudde, J. P., Wichert, J., Large, D., López-Munguira, A., & Cnudde, V. (2016). Roofing slate standards: A critical review. Construction and Building Materials, 115, 93-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.042

Cárdenes, V., Rubio-Ordóñez, Á., & Ruiz de Argandoña, V. G. (2020). Definition of roofing-slate lithotypes for an international roofing-slate classification. Key Engineering Materials, 848, 48-57. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.848.48

Cárdenes, V., Rubio-Ordóñez, Á., Wichert, J., Cnudde, J. P., & Cnudde, V. (2014). Petrography of roofing slates. Earth-Science Reviews, 138, 435-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.07.003

Checkatrade. (2024, January 4). Ceiling water-damage repair cost guide. Retrieved 16 June 2025 from How Much Does Ceiling Water Damage Repair Cost in 2025? | Checkatrade

European Committee for Standardization (CEN). (2014). BS EN 12326-1:2014. Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding – Part 1: Requirements. Brussels, Belgium.

European Committee for Standardization (CEN). (2011). BS EN 12326-2:2011. Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding – Part 2: Test methods. Brussels, Belgium.

European Committee for Standardization (CEN). (2005). BS EN 12326-3:2005. Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding – Part 3: Code of practice. Brussels, Belgium.

FluentCargo. (2025, May). Route calculator: Santos (BR) → London Gateway (UK); Vigo (ES) → London Gateway (UK). Estimated emissions: 705 kg CO₂e and 171 kg CO₂e per TEU (24 t). Retrieved 16 June 2025 from https://www.fluentcargo.com

López-Mesones, F. (2016). Study on the behaviour of lithostatic-compression ‘slates’ under freeze–thaw and thermal-cycle actions (in Spanish). O Barco de Valdeorras, Spain: Slate Cluster of Galicia. (Cluster da Pizarra de Galicia)

National Federation of Roofing Contractors. (2023). Guidance Note GN 66: Brazilian slate (Rev. 02). London, UK: NFRC. Member-only document, accessed 10 June 2025.

National House Building Council. (2012). Technical Extra 07. Milton Keynes, UK: NHBC. Retrieved 16 June 2025 from Technical Extra Issue 07 pdf – NHBC Home

PistonHeads. (2020, May 5). Brazilian slate issues on new-build house [Forum post, Homes & DIY]. Retrieved 16 June 2025 fromPistonHeads UK

Roof Tile Association. (2019, March 15). Choosing roofing materials suitable for the UK climate. Retrieved 16 June 2025 from Choosing roofing materials suitable for the UK climate – Roof Tile Association Roof Tile Association

Stone Federation Great Britain. (2011). Natural stone: The oldest sustainable material (PDF). London, UK: SFGB. Retrieved 16 June 2025 from https://www.stonefed.org.uk

Stone Federation Great Britain. (2011). Selecting the correct stone. London, UK: SFGB. Retrieved 16 June 2025 from Selecting the Correct Stone – Stone Federation GB