Natural slate has been a building material of choice for many centuries, with architects, developers and roofing contractors continuing to rely on it for roofing systems.

The complete handbook for natural slate: your go-to guide for roofing

This guide seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of natural slate, including information on its origins, the various types available on the market, how it is extracted and processed, and the benefits that can be derived from using it when compared to alternatives such as concrete and clay tiles.

Additionally, it will outline the key certifications to look out for, as well as offering advice on the installation and cleaning of slate roofs.

The guide is presented in the following sections:

What is slate?

By definition, slate is a dark grey, fine-grained, metamorphic rock produced through the compression of various sediments that can be easily divided into thin layers. These thin, small, flat pieces of rock are used for various purposes, such as roofing construction.

While this definition of slate is well acknowledged, it is not globally ubiquitous.

Across the world, ‘slate’ is made from different sources and rock formations, meaning different slate products have varying characteristic in relation to strength and water absorption.

Understanding true slate

True natural slate is a layered metamorphic rock of great strength and durability that can be split cleanly along planes of cleavage. This kind of slate begins life as fine clay and sediments such as sand or volcanic dust – these gradually amalgamate over time via lithostatic compression (pressure from above) to form a sedimentary rock called shale.

When exposed to high pressures and temperatures known as tectonic compression, shale will undergo metamorphism. This is structural change caused by differing conditions to those in which that rock was originally formed, with the end result being perfectly layered natural slate.

What is the difference between slate and shale?

It is difficult for the naked eye to differentiate between slate (metamorphic rock) and shale (sedimentary rock). Both break apart in layers and both develop in the same range of colours.

One of the key differences, however, lies in the fact that shale splits along its original bedding plane, while true slate splits along the plane of cleavage developed during the tectonic compression.

This results in a stark difference in characteristics. While true, foliated tectonic slate is highly durable, has a high bending strength, is waterproof with low water absorption and also fire resistant, shale is considerably softer and far less water resistant.

What does this mean in terms of application?

The characteristics of true slate make it an ideal material for parts of buildings which are exposed to adverse weather conditions, such as roofing, cladding and paving. Shale, on the other hand, is not suitable for such applications.

Despite this, sedimentary rocks like shale are sold as ‘slate’ products in countries such as Brazil and China, despite not being metamorphosed and therefore lacking in the strength and durability of true slate.

It is important for contractors to avoid these products. While cheaper alternatives can be attractive from a cost perspective, it is imperative that only quality tectonic slate is used in order to achieve long-lasting, durable solutions for roofs and façades.

This is proven by the fact that many high-quality slates from the 1800s are still in use and serviceable today.

Origins and types of slate

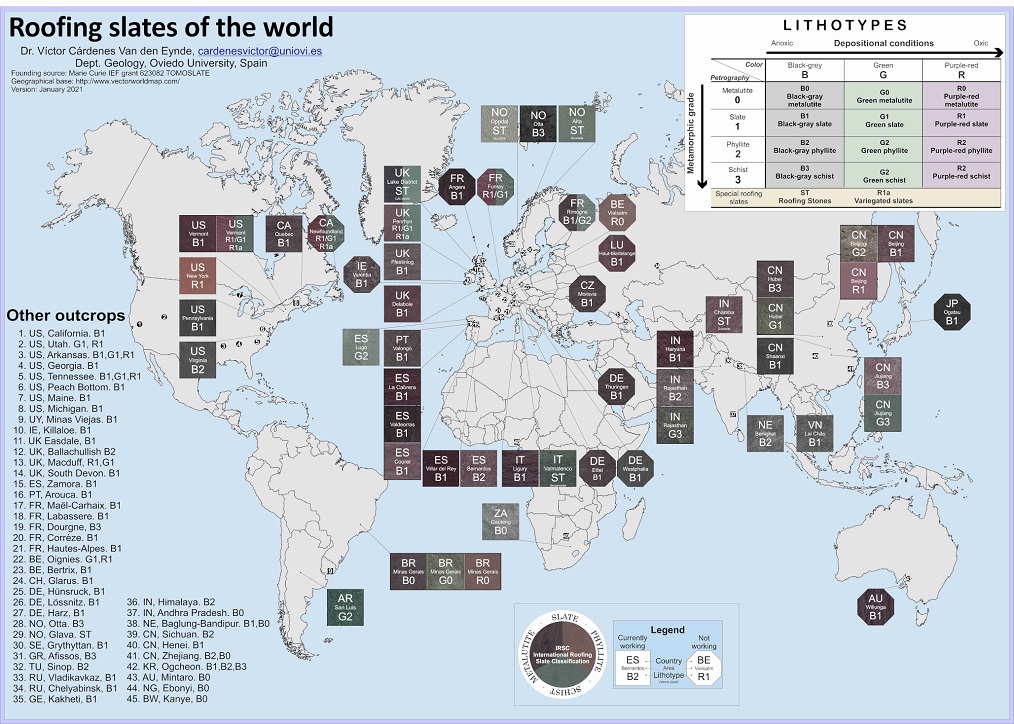

Click on the image to see the roofing slate outcrops map in large

Fast forward to the 1800s, and the slate industry began to expand rapidly in tandem with population growth, paving the way for a quarrying boom in other countries. As such, there are several different types of slate that can now be sourced from countries around the world, each with varying characteristics and colours that occur from differing slate compositions. Here are some of the most renowned:Welsh slate

While the distinctive Welsh blue/purple Penrhyn slate is highly durable, easy to work with and low maintenance, the country’s most popular forms of slate are Penrhyn Heather Blue and the dark blue-grey form Cwt-y-Bugail.Scottish slate

Scottish slate is a prominent feature of the country’s many historic buildings. Scotland’s two slate outcrops in Ballachulish and the Slate Islands produced a thick slate known for its traditional and rugged aesthetic. However, slate is no longer quarried in the country and so, as a result, many quarries around the world offer look-a-like alternatives to enable stylistic continuity for new builds, refurbishments and repairs.English slate

Just like it’s Welsh and Scottish counterparts, England offers some indigenous slates. Below the Scottish boundary there is a slate outcrop in the Lake District where you can find grey and green rough roofing slate, known as Cumbrian slates. In Cornwall there is also the Delabole quarry which produces a dark-grey slate, occasionally of green hue.Canadian slate

Also offering blue-grey and heather purple shades, Canadian slate is often used as a substitute for Welsh slate. Among the most popular variants are Glendyne – a blue-grey slate from Quebec that closely resembles Welsh slate.Spanish slate

While Spanish slates do not have the same diversity of colour as the UK’s slate outcrops, they are of incredibly high quality and from the biggest slate outcrop in the world. Spanish slates tend to be black grey in colour and fine grained. Although various forms of slate and shale can be sourced globally, Spain is the world’s largest slate producer. In fact, it’s estimated that CUPA PIZARRAS slates account for approximately a quarter of the world’s supply, with 20 quarries and 24 processing plants to its name.

Although various forms of slate and shale can be sourced globally, Spain is the world’s largest slate producer. In fact, it’s estimated that CUPA PIZARRAS slates account for approximately a quarter of the world’s supply, with 20 quarries and 24 processing plants to its name.

Brazilian Slate

Brazil is the second largest producer of slate in the world and 95% of Brazilian slate comes from the Minas Gerais region in the south east of the country. However, slate from Brazil is often not considered a true slate as it hasn’t undergone the metamorphic process. As such it is sometimes referred to as shale or sedimentary mudstone and has a very flat, uniform surface that can be prone to breakage along the bedding plane.Chinese Slate

Similarly to Brazilian slate, slate quarried in China is often considered a shale, and not a true slate. The range of colours available is very broad, but colour loss has been recorded on low quality products along with structural failure.What’s the difference between phyllite and slate?

Phyllite refers to a group of minerals, the phyllosilicates, which are very abundant in the earth’s crust. They have a flat, sheet form and typically contain other minerals such quartz, feldspar and sometimes small amounts of carbonates and iron sulphides.

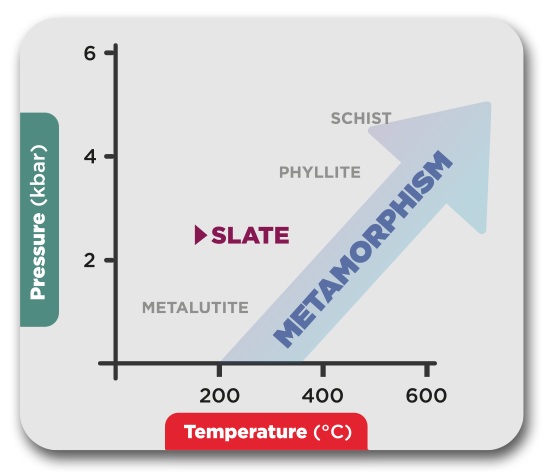

Metamorphic series of “roofing slates”, from metalutites, of a lower grade, to mica-schists, of a higher grade. The rocks that give the best result are slate and phyllite.

Like slate, phyllite is a metamorphic rock that is formed when pressure and temperature act on shale to a higher degree and for a longer period of time than is necessary to create slate. While slates and phyllites naturally have common properties, largely differentiated by the higher metamorphic grade of phyllites, there are some differences. Phyllite has greater crystallinity as it features larger mica flakes than those found in slate. These help to make the surface of the phyllite brighter and its layers more defined; however these flakes also affect the rock’s porosity, meaning phyllite has a lower level of water absorption when compared to slate. Meanwhile, from a mechanical point of view, phyllite is harder than slate but has a lower flexural strength.

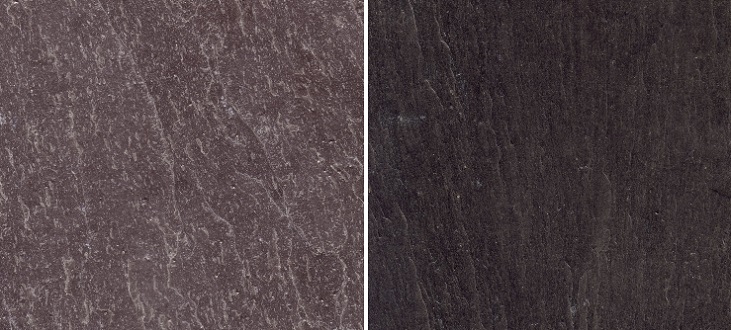

Left image: typical slate texture, fine-grained and homogeneous. Right image: phyllite texture, where the superficial scales can be seen, resulting from the higher metamorphic grade.

Despite these differences, both rocks offer similar values and performance, and can last for several hundred years under ideal conditions.Roofing slates formats and sizes

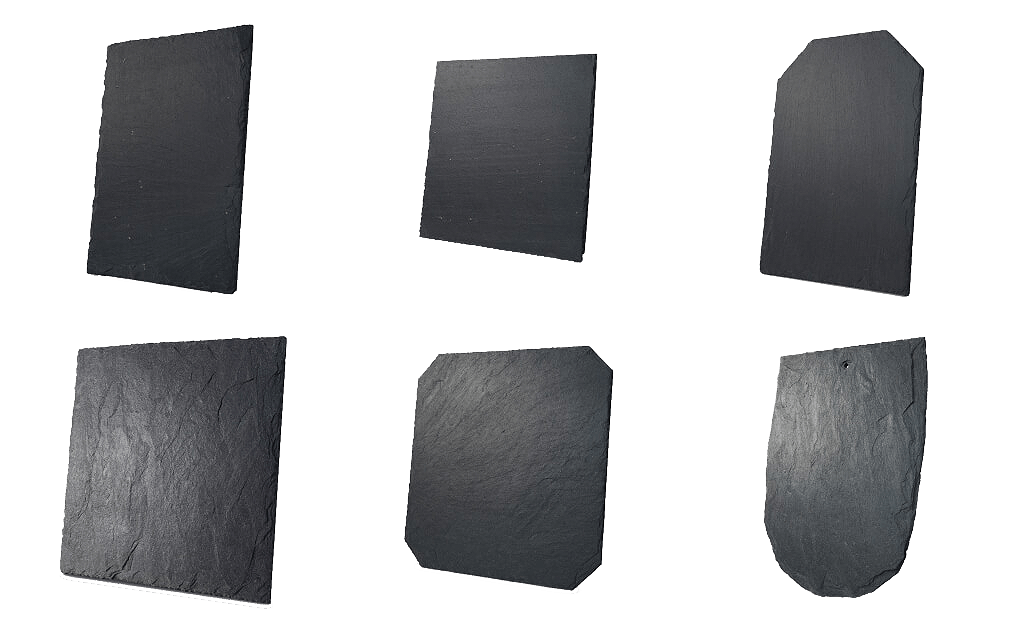

Natural slates are produced in a vast array of sizes, formats and models.

While rectangular is the most typical slate format, many roofs also use slate in other formations such as square, rhombus, and bullnose.

Interestingly, the slate used in each geographical area will vary owing to differences in climate, culture and/or tradition.

Some examples of slate formats. In order: Rectangular, Square, Innova, Lauze, Losange, Bullnose

As an example, areas close to quarries typically use slate that is low in quality and small in size, with higher quality and larger pieces often being sent to cities – something that is typical around the quarries in the northwestern regions of Spain. This is because better, larger materials provide a greater application range, and are therefore in higher demand.

Another example would be climate factors. Coastal regions, for example, typically use smaller and thicker slates as these are able to better withstand high winds and adverse weather conditions.

Further, there can simply be cultural differences. In France, for example, smaller slates are used as standard, while in Germany thicker slates have often been used owing to the regular incorporation and creation of decorative designs.

Slate variation in England and Wales

In England and Wales, the most commonly used slates are 600mm x 300mm and 500mm x 250mm with a thickness of between 4mm and 6mm being favoured. This general standardisation was brought in during the Victorian period when the expansion of the railways enabled slate quarried in Wales to be transported around the UK and beyond to other countries. As a result of this export process, slate was cut to the sizes preferred by roofers in areas like London where the wind and rain are less extreme and larger slates are favoured.

However, local and regional traditions still persist, particularly in relation to historic structures. Generally, the more extreme the weather of the region, the smaller and thicker the slates used and the greater the headlap – intended to provide extra protection against driving rain. For example, in the northeast of England, smaller slates of 400mm x 250mm are traditional, while Welsh slates used locally can be up to 9mm thick.

Slate variation in Scotland

Unlike in Wales, Scottish slates were more often used domestically and not exported. Consequently, they were cut to varied and random sizes. This resulted in the tradition of laying slates in diminishing courses in order to minimise waste. This practice involves laying the largest slates near the base of the roof, with the slates decreasing in size up to the ridge of the roof.

Scotland has traditionally favoured thicker slates than other parts of the UK as the added weight reduces the likelihood of the slate being dislodged in windy conditions. The tops of Scottish slate are also often trimmed to form ‘shoulders’, this allows for the slate to be rotated around the nail once in place so that, should a slate come loose, another can be fitted into position without the need to remove a section of the roof.

The Scottish baronial style of architecture in the nineteenth century also had an impact on the slate in the country. The style’s affinity for turrets, towers and surface decoration resulted in the need for smaller slates that could be easily laid to match the arc of a curved roof; this combined with slates cut to shapes such as scallops produced highly decorative and unique roofs.

Frequently asked questions

How long does a slate roof last?

If properly looked after, high quality slate roofs can last centuries. In fact, there are plenty of examples of slate roofs that were originally installed in the 19th century that are still present and in a serviceable condition today.

Is a slate roof expensive?

Generally speaking, it is easy to find cheaper alternatives to natural slates such as concrete or fibre cement slates.. However, there are a number of factors that can make natural slate more competitive including; the breathability of slate and the number of battens needed as well as the fact that the durability and lifespan of slate is far superior.

Roofing installed with slate can last up to 150 years if properly maintained. At CUPA PIZARRAS, we offer warranties of up to 100 years on natural slate products. By comparison, concrete tiles have a lifespan typically set by manufacturers at roughly 30 years.

Therefore, while the upfront cost of natural slate is typically higher, the longevity of the material results in a lower lifetime cost versus alternative materials.

How much does a slate roof weigh?

A standard piece of slate sold in England and Wales measuring 500mm x 250mm would weigh approximately 1.9kg, equating to approximately 37kg per square metre.

If we compare that with a concrete tile that attempt to replicate the characteristics of slate, the weight rises to around 50kg per square metre, creating a much higher load across an entire roof. With heavier alternatives such as concrete, timbers and structural features need to be stronger, which can often lead to additional costs.

What cleaning and maintenance does natural slate require?

While slate itself doesn’t require any active maintenance, environmental factors can influence it which need to be addressed. A range of materials can be deposited on a roof from the atmosphere, providing an environment in which mosses may begin to grow on the slate. If left unaddressed, these mosses may cause problems such as the blocking of roof gutters and/or the potential for water ingress into the roof.

In this sense, while slate itself doesn’t require maintenance, a slate roof may need regular treatment to prevent issues from arising.

Production process

From pre-quarrying and extraction to refinement and traceability, there are multiple processes that are required to take slate from the quarry to its finished state as a roof slate. Here, we outline each of the key steps involved.

1 – Before quarrying

Before anything else, geological, mineral and geotechnical surveys need to be carried out to ensure that any quarrying activities are targeted in the optimum areas. Critically, these are also accompanied by prospection work and sample testing to determine both the quality of the slate and potential reserves of the deposit.

It’s also important to carry out regular surveys throughout the life of exploitation in order to prepare the quarry for the future and guarantee a continuous production of high-quality slate.

2 – Extraction

When the presence and quality of slate has been verified through surveys, extraction can begin. Typically, natural slate will first be surface quarried – the oldest and easiest way to extract slate. In areas where the highest quality slate deposits are not accessible from the surface, mining is the most efficient method of extraction. This is a rare occurrence, however, due to the complexity of the process and the increased cost.

To begin extraction when quarrying, the ‘overburden’ (fragmented, unusable material) must first be removed. Thereafter, slate can be sawn from the quarry face in large flat slabs known as ‘rachones’ using a diamond beaded steel cable. This technology enables natural slate to be extracted without damage while also increasing yields versus former dynamite methods.

These slabs of slate are then carefully cut into smaller natural slate blocks and loaded into trucks before being transported to processing plants (often situated nearby) where further refinements take place.

3 – Processing

Upon arriving at the processing plant the slabs of slate are inspected by on-site experts and sorted based on their quality and potential. Following this, slabs will be further sawn across their natural ‘cleavage’ planes into smaller blocks.

Traditionally, these blocks are passed onto skilled craftsman who will work using a hammer and chisel to split the slates into the desired thickness. However, owing to skill shortages and technological advances, the splitting and refinement of slate is becoming increasingly automated – an evolution that will continue moving forward.

With the finished thickness achieved, the edges of each slate are then “dressed” by a machine to give the traditional chamfered edge and exact finished size, ready for final inspection and sorting.

4 – Inspection and grading

When the cutting and crafting process is finished, each slate is assessed by a quality control team based on technical and aesthetic guidelines that allow the slate to be classified in three different selections.

- R Excellence selection: Considered to be the best natural slate produced in the world, only pieces with high flatness and very regular thickness pass for R Excellence.

- H selection: Characterised by its high quality, with only slight differences in the flatness and thickness of the piece, these are often selected by expert installers for high quality roofing finishes.

- Natural selection: While the technical characteristics of natural selection slate are the same as those in superior selections, this selection allows for greater variations in thickness and flatness.

These quality assurance procedures are vital in ensuring that any specified slate meets or exceeds the quality and longevity requirements of its application. Critically, the slate quality is certified by IQNET with its ISO 9001:2000 Standard.

5 – Shipping and traceability

Once graded, natural slates are counted and packed vertically in crates. At CUPA PIZARRAS, each and every pallet is then barcoded and labelled ahead of transportation and shipment.

These labels include a description of the slate comprising the quarry and plant of origin, format, thickness and name of the person in charge of selection. This ensures accountability over the quality of the slate, the ability to reorder colour matched slate from the same quarry, and the ability to verify quality.

Why use slate?

Natural slate has been used for roofing applications for hundreds of years and continues to be a popular choice within the building industry. Indeed, as time has passed and our knowledge of how to use and form slate has grown, the variety of applications that slate fulfils has grown markedly – well beyond traditional pitched roofing.

Natural slate has numerous beneficial qualities and properties that explain its popularity and longevity as a key building material. Here, we will outline the main reasons why the industry continues to rely on it.

Slate is an extremely versatile building material

Natural slate is suitable for a wide range of designs, structures and architectural styles – both traditional and modern.

This is because it is an extremely flexible and workable material. Slate can be easily cut onsite into a variety of shapes and sizes to help complete intricate details. That said, the most common slate format in the UK remains the standard rectangle, although the choice open to architects and construction professionals is vast. Manufacturers now commonly offer shapes such as bull-nose and half-moon, allowing for unique elements to be crafted with ease, as is commonly seen in Germany and other European markets.

In regard to traditional pitched roofing, a wide variety of roof shapes can be achieved using natural slate – from m-shaped to gambrel and Dutch to butterfly. Features such as hips, valleys, gables and dormers can be incorporated with relative ease, and through adding characteristics such as steep pitched and extended floating gables, a natural slate roof can be elevated from a functional necessity to a standout building design feature.

However, applications extend far beyond the traditional pitched roof.

For example, natural slate can also serve as a sleek and striking cladding material and is even suitable for use on flat roofed buildings. Furthermore, as a lightweight alternative to brick, natural slate cladding is ideal for structures where material weight is a concern, a good example being where a building or part of a building is leaning.

Another design trend gaining traction is the use of slate on building interiors. Slate-based feature walls are a great way of connecting the indoors and outdoors, and some architects are even using the material to complement and enhance a biophilic design approach.

Slate is hard wearing and resistant to the elements

As well as being extremely versatile, natural slate ticks many boxes around practicality and endurance.

Its lifespan is markedly longer than alternative roofing materials, not least because it is not damaged by the likes of fungi, moss, insects, animals and birds. Slate is also resistant to the elements and can withstand extreme weather conditions – and because it is waterproof, it is resistant to damage caused by the freeze thaw process during colder periods.

The upshot of this is that slate requires little to no maintenance, with its colour and properties sustaining their original integrity throughout the entire lifecycle.

Slate has first-rate fire safety

Natural slate’s A1 rated non-combustibility is another important selling point. Put simply, slate is one of the most fireproof building materials available. This is because slate is made of quartz, mica and chlorite, minerals which do not burn or ignite with increasing temperatures.

The melting point of quartz is around 1,600°C, with mica and chlorite melting at temperatures between 1,000°C and 1,400°C. Household fires reach temperatures of around 800°C.

Several studies have been conducted in the fire performance of slate, and all of them show that slate is a material that does not burn.

Slate is a sustainable solution

In addition to fulfilling important performance and visual requirements, slate is also a 100% natural material that carries a low environmental footprint.

After it has been quarried or mined, slate requires little processing before it can be used on a roof, a fact that compares very favourably against alternative roofing materials. Indeed, the production of slate creates significantly less air pollution and requires the consumption of less water than the likes of clay, concrete and limestone tiles, copper and lead.

More detail on the sustainable credentials of natural slate can be found in the next section.

Sustainability

The building sector contributes around a quarter of UK emissions according to estimates made by the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC). With targets in place to transition to net zero by 2050, action is needed to reduce the environmental footprint of our building stock, both in terms of existing buildings and those in the construction pipeline.

While operational carbon – the emissions associated with operating a building (heating, lighting, power etc) – tends to grab the headlines, more attention is being paid to embodied carbon, which is expected to account for 50% of built environment emissions by 2035 as buildings become more efficiently run.

Natural slate as a low-carbon roofing material

Architects and constructors are therefore seeking materials which will help to minimise the environmental footprint of their projects.

Natural slate is a mineral product with a highly efficient production process from the quarry through to installation. Much of the process is still carried out by hand and water is often the only treatment necessary to get the product ready for sale. Clay tiles, on the other hand, are kiln fired and thus require large amounts of energy to turn them into a durable material.

Indeed, according to an independently verified Life Cycle Analysis (LCA), natural slate is the roofing material with the lowest carbon footprint throughout its useable life.

Meanwhile, research conducted by the University of Bath as part of its Inventory of Carbon and Energy (ICE) project also found slate to measure favourably against alternatives such as clay, concrete and limestone tiles, copper and lead. The embodied carbon per square metre of roof area (KgCO2/m2) was calculated for each material. Slate measured at 0.15-1.62KgCO2/m2, significantly lower than concrete (10KgCO2/m2), clay (27Kg CO2/m2), copper (20 – 28KgCO2/m2) and lead (41KgCO2/m2).

Furthermore, natural slate also requires less water and energy and pollutes less than other roofing products during its production process:

- Water consumption: Slate production uses 11 times less water than fibre cement, 135 times less water than zinc and half the amount of clay.

- Energy consumption: Slate production uses 6 times less energy than fibre cement, 4 times less energy than zinc and half the energy of clay.

- Air pollution: Slate production generates 6 times less pollution than fibre cement, 4 times less pollution than zinc, half the pollution of clay.

The relative lifespan of materials should also be taken into account when considering embodied carbon. Natural slate is an incredibly hard rock and can be guaranteed for 100 years by some producers, whereas a clay tile typically has a usable life of 30 to 60 years with varying degrees of quality.

The longevity of natural slate also means that it can be reclaimed and reused. This promotes circular resource management, an important principle that keeps materials in use for as long as possible through reuse and recycling.

Find out more about the sustainability of slate.

Choosing the right slate supplier

CUPA PIZARRAS fully embraces circular principles and takes sustainability incredibly seriously.

When it comes to embodied carbon, we are fully aware that the individual practices of a supplier can have a dramatic effect on a product’s embodied carbon value, even if the materials used were low in embodied carbon prior to the point of production.

CUPA PIZARRAS is a certified carbon neutral company according to the PAS 2060 standard, offsetting the CO2 emissions caused by its operations through contributions to tree planting projects in the UK and schemes which protect the Amazon rainforest. The company is also ISO 14001 certified, demonstrating a commitment to monitor and minimise environmental impact.

These are pioneering feats. CUPA PIZARRAS was the first company in the slate industry to commit itself to measuring and reducing carbon emissions and has been awarded a Gold EcoVadis rating for the past three years. CUPA PIZARRAS, as part of Cupa Group, was ranked in the top 5% of companies measured across a wide variety of sustainability markers.

Learn more about CUPA PIZARRAS as a sustainable supplier.

Quality certifications and standards

Spain is by far and away the most prolific producer of slate in the world. Some 90% of global sales are fulfilled here, with the northwest of the country being the primary source of production.

Spanish slate sets the benchmark for several reasons. Due to its tectonic origin, it is recognised worldwide for its performance, high quality and superb aesthetic finish, thus making it a roofing material of choice for architects and housebuilders.

However, before specifying any slate, you should ensure that it conforms to the relevant certifications and standards. There are numerous certificates and standards that can validate the quality of a slate product; but as more than 95% of roofing slate is traded in Europe and North America and so the technical requirements laid out in these region’s relevant standards are most often referenced.

Standards used in Europe

In Europe, the minimum standard for slate is BS EN 12326-1:2014: Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding – Part 1: Specifications for slate and carbonate slate. This was brought in during the 1990s to replace individual standards in countries such as France, Italy and Spain whose tests all reflected the differing architectural styles and qualities of rock quarried in that region.

Since 2006, it has also been mandatory for all slate bought and sold in the EU to have a CE mark attached to the pallet that gives information about the quality of the slate in relation to EN 12326. In the UK, companies can use a UKCA mark instead of, or in addition to, the CE mark but both have the same significance as a demonstration of compliance with EN 12326.

Furthermore, some other regional standards still exist in addition to EN 12326. In France, the body responsible for the certification of slate still uses its own quality mark, the NF 228; Belgium similarly retains its own ATG mark. In both these cases the test methods of the EN 12326 are used, but with more restrictive parameters. This is designed to stop the sale of lower quality CE marked slate.

Standards used outside of Europe

Brazil, despite being the second largest producer of slate in the world, does not have its own standard. It was, however, incorporated into the EN 12326 in 2010 when the definition of slate was adjusted to facilitate the sale of Brazilian products.

In the USA and Canada, minimum technical requirements are compiled under the ASTM C406 according to the results from three test methods. Under this standard an expected service life is provided, an addition that is not part of the EN standard.

China and India have also developed their own standards for slate in recent years after significant growth in the industry. The Chinese standards BG/T 18600 are more internationally focused drawing on the EN and ASTM and reflecting the growth of Chinese slate on the international market. The Indian Standard IS 6250 is focused primarily on the domestic market as there is little market for export at the current time.

What should you look for in a slate supplier?

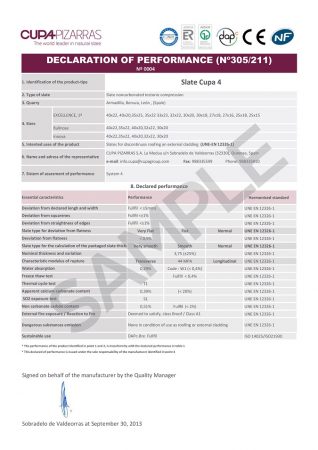

Before committing to a supplier, it is crucial to examine updated documentation from the producer which demonstrates the performance of their natural slate.

Roofing slate suppliers should provide a Declaration of Performance (DoP) document – this provides clarification of the product’s performance and is classified in accordance with BS EN 12326.

In DoP documents, the highest-quality slates will be confirmed as adhering to first-class performance across a range of characteristics. In particular, look out for the letters A1, S1, T1 and W1:

- A1 (Reaction to fire): Non-combustible material.

- S1 (Sulphur dioxide exposure): No observed damage after exposure to sulphur dioxide solution.

- T1 (Thermal cycle code): No changes in appearance. Surface oxidation of metallic minerals. Colour changes that neither affect the structure nor form runs of discoloration.

- W1 (Water absorption): Absorption rate of less than 0.6%. Most CUPA PIZARRAS slates perform at 0.4%.

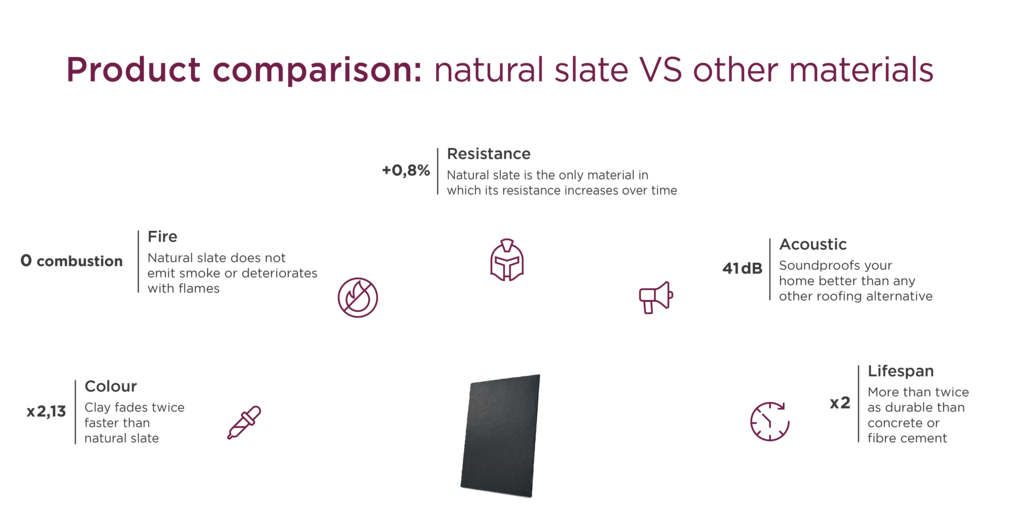

Material comparisons

The most common alternative roofing materials to slate include fibre cement, clay and concrete.

Before choosing which material to go for, it is important to consider how these various choices measure up across key performance characteristics. Here, various data and tests point to the superiority of natural slate.

Durability of colour

Natural slate does not suffer from noticeable deterioration of colour. Even in the coldest environments, its colour remains the same while other materials are prone to losing their pigmentation considerably over time.

Compared to slate, fibre cement, clay and concrete lose more colour after 600 frost-thaw cycles:

- Fibre cement: 1.03 times the colour loss of slate.

- Clay: 2.13 times the colour loss of slate.

- Concrete: 2.61 times the colour loss of slate.

Durability of sheen

Natural slate also retains its distinctive sheen throughout its lifecycle, performing far better than other roofing materials after 300 frost-thaw cycles:

- Fibre cement: 3.29 times the sheen loss of slate.

- Clay: 3.38 times the sheen loss of slate.

- Concrete: 8.63 times the sheen loss of slate.

Resistance to cold conditions

Over time, natural slate actually gains strength. This means it can endure the elements better than alternative materials as years go by, as shown by tests on resistance variation in cold conditions.

After 600 frost-thaw cycles, natural slate increased its resistance by 0.8%, while fibre cement (-12%), clay (-4.2%) and concrete (-13%) all lost strength during the same period.

Fire resistance

Natural slate is also incredibly resistant to fire, making it one of the safest roofing materials on the market.

Indeed, it is the only solution which does not release smoke or deteriorate when in contact with fire. This has been proven by a flammability test carried out according to the norm UNE EN ISO 11925-2, where slate was compared to a range of alternative materials:

- Natural slate: No emission of smell, smoke or particles. No expansion of trace diameter.

- Concrete tiles: No emission of smell, smoke or particles. 26mm expansion of trace diameter.

- Fibre cement tiles: Emission of smell, smoke or particles. 31mm expansion of trace diameter.

- Steel tiles: Emission of smell, smoke or particles. 100mm expansion of trace diameter on both sides.

- Aluminium tiles: Emission of smell, smoke or particles. 49mm expansion of trace diameter on both sides.

- Zinc tiles: Emission of smell, smoke or particles. 68mm expansion of trace diameter on both sides.

Lifespan

Natural slate is a popular roofing choice among architects and homebuilders because it is extremely long-lasting, providing numerous benefits around quality, cost, maintenance and sustainability.

It has an average lifespan of 75 years, with some manufacturers even offering guarantees of 100 years of usable life. This compares extremely favourably to other roofing materials, the following figures having been obtained from manufacturers:

- Fibre cement: 48.75 years

- Clay: 52.5 years

- Concrete: 47.5 years

Soundproofing

Roofs are an important sound buffer and can help make a home healthy in terms of noise pollution.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a healthy level of night-time traffic noise to be heard inside a building is 45 decibels or lower.

Natural slate, when tested for acoustic intensity produced by rain, falls well under this level at 41 decibels, making it one of the most effective roofing materials for cutting out noise. As a comparative example, metal-based roofing systems made from zinc (52 decibels), steel (57 decibels) and aluminium (57 decibels) all test higher than the WHO’s benchmark.

Design and applications

Natural slate has been used as a building material for millennia thanks to its combination of durability, the ease with which it can be split and the uniformity of its colour and appearance. The Romans were the first to cut slates into shingles and since then it has been favoured by a variety of builders and architects working in many different styles and on many different building typologies.

Roof pitches

Pitched roofs have traditionally been favoured when using slate because an A-frame roofing system sheds water most effectively. The angle of the pitch varies depending upon the exposure of the site, the length of rafter and the height of the building.

The National House Building Council (NHBC) indicates that the minimum pitch for a slate roof should be 20 degrees, subject to the headlap. BS 5534 agrees with this, where a project is located in an area of moderate exposure and the slates are 500mm with a 115mm overlap.

Mansard Roofs

A mansard roof, popularised in the 17th century by architect Francois Mansart, is a hipped gambrel roof that provides extra living space within the roof itself. In the UK, a mansard roof is considered a wall under The Building (Amendment) Regulations 2018 when the roof is pitched at an angle of 70 degrees or more.

As a result, the structure must adhere to regulations governing the construction of walls and not roofs – including those regarding the combustibility of materials used. Natural slate, however, still provides an excellent solution for mansard roofs as a cladding system can be combined with a traditional hipped roof to provide a seamless and imposing design feature.

Rainscreen cladding

Natural Slate cladding systems have some history in slate producing areas but have only recently gained more widespread popularity. The characteristics that make slate an excellent roofing material apply to cladding also, with its uniform finish, durability and possible sizing variations all enabling it to be utilised as a striking rainscreen cladding.

CUPACLAD rainscreen cladding system combines natural slate with a metal bracket installation method to provide a lightweight and easy to install cladding that simultaneously provides a contemporary finish and a nod to vernacular styles and materials. With the metal support structure, the CUPACLAD® system also provides an A1 non-combustible cladding system, unlike many alternative materials. This means it’s ideal for use external on walls and mansard roofs over 18 metres above ground level.

Installation and cleaning

Natural slate carries many advantageous qualities which make it a roofing material of choice for architects and building developers.

To fully exploit these benefits, it is crucial that the design and installation of slate roofing is optimised – that means careful planning and paying close attention to several facets at every stage of the project. Failure to do so can compromise on performance.

When installing a natural slate roof, there are many key factors that need to be considered, both in terms of the design and execution of the works. The most significant are outlined here:

- Grading: Once removed from their pallets, slates need to be graded and sorted into three or four thicknesses. BS 8000 Part 6 2013 Code of Practice for Slating and Tiling states that the process of sorting slates by thickness is as important as the fixing process. If stacked on site, they should be laid on the long side with battens between the layers. During grading it is also important to tap each slate to confirm its soundness. The slates should then be installed with the thickness decreasing from the lower eaves with the thinnest slates at ridge level. Grading gives the roof an improved aesthetic finish and stronger resistance to wind lift.

- Batten sizes: Battens are lengths of wood that are laid in between rafters to secure the roofing felt – a crucial part of the process of preparing the roof for slate. Getting the batten size right (especially its width and depth) is crucial, as this will ensure a suitable anchor to hold the slates in place. Battens also play a part in the durability, rigidity and weather tightness of the roof system. The minimum size of a batten for slating is 25x50mm.

- Spacing: It is important to leave gaps between slates to allow the underlay to take some of the wind uplift load (as opposed to the slate itself). A gap of between 3mm and 5mm between each slate is recommended – any larger than this and there will be a risk of insects and bats entering the roof.

- Exposure/environment: Exposure to wind and rain will play a central in the design of a slate roof. For example, buildings positioned on slopes, hills or coastal areas, as well as tall buildings, will be graded with higher exposure. Exposure will also impact the type of slate used. Typically, small slates are more suitable for steep roofs, with wider or thicker slates used on more exposed sites and lower roof pitches.

- Pitch: The pitch for a slated roof will depend on the exposure of the site, the length of the rafter and height of the building. The pitch may also impact the method of fixing – for example, hook fixings should not be used for any pitch that is below 25 degrees. Features such as mitred hips, meanwhile, should not be considered on roofs with a pitch of less than 27.5 degrees.

For more detailed information, see CUPA PIZARRAS’s comprehensive Roofing Design and Fixing Guide.

The importance of cleaning

Natural slate requires little to no maintenance once it is installed, providing a secure, high-quality and aesthetically pleasing roof which can last without issue for decades, even centuries.

However, to protect the building from water ingress and other performance hazards, cleaning moss and other deposits from the roof is important. Furthermore, cleaning helps to maintain the aesthetic appearance of slate roofs.

Most cleaning tasks should be achievable with a pressure washer. That said, slate roofs are not designed to be walked on, so take great care when moving around. It is also recommended to avoid applying pressurised water from the bottom upwards, as this will result in water (and the debris in question) being blasted under the roof.

Click here for a full guide to slate roof cleaning.